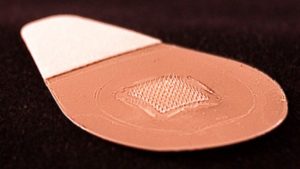

Each solid, water-soluble micro-needle is just long enough to penetrate the skin. The vaccine is released as the needles dissolve completely over a few minutes.

Dr. Nadine Rouphael, associate professor at Emory University School of Medicine and lead author of the trial, explained how it works:

There is an audible snap that you hear when you apply enough pressure to ensure that the microneedles will actually penetrate the skin. … After few minutes, we remove the patch. By then, those microneedles will be completely dissolved within the skin, along with the vaccine.”

The researchers enrolled 100 adult patients and gave 50 of them a flu vaccine patch. The patients who used the patch reported more itchiness and redness, but less pain than patients who had a flu shot.

The vaccine patch also produced a similar antibody response as the flu shot, and the immune responses were still present 6 months later. About 70% of patients who received the patch said they preferred it over a shot.

Larger studies will be necessary to determine if the flu vaccine patch is equally effective at preventing flu illnesses as a traditional flu shot. Even if the flu vaccine patch works and does not cause serious side effects, it will be several years before it is sold to the general public.

Yet in the future, Dr. Rouphael said she believes the patch will be useful. It does not need to be refrigerated, which is a big advantage in countries where access to electrical refrigeration is unreliable.

Another advantage is that the vaccine could be sent in the mail and self-administered by a patient, which would reduce healthcare costs and help people avoid getting the flu at a hospital or a doctor’s office during a major flu pandemic.

The National Institute of Health (NIH) funded the study and it was published in the medical journal The Lancet by researchers at Emory University and the Georgia Institute of Technology.